A framework for token value flows

Level up your open finance game five times a week. Subscribe to the Bankless program below.

Dear Bankless Nation,

We’ve talked about protocol tokens before. We call them crypto capital assets.

Why? Because the tokens can represent both economic and governance rights over a protocol. Like equity in a company but settled onchain, not in meatspace.

Jon nails it here—first he shows us a three-tier framework for token value flows:

- Protocol Volume: total dollar value of demand

- Protocol Revenue: cost charged to users and captured by protocol

- Protocol Divvy: revenue distribution to market participants

Then he goes deep into the most interesting part—the protocol divvy.

Token Value Flows

Turns out these protocols operate more like co-ops than like traditional companies. They can programmatically divide reward between users, validators, governors, liquidity providers, and other supply side contributors to bootstrap themselves.

The design space for protocol tokens is massive.

We’ve entered an exciting timeline. Every asset class is about to be remade.

That’s why we’re going bankless—this is the new world.

- RSA

🙏Sponsor: Aave—earn high yields on deposits & borrow at the best possible rate!

🎙️ NEW PODCAST EPISODE

Listen to episode 26 | iTunes | Spotify | YouTube | RSS Feed

WRITER WEDNESDAY

Guest Post: Jon Itzler, Research Intern at Accomplice

On protocol tokens & on-chain cash flows

This paper aims to lay out a framework for protocol-generated value flows, the sets of stakeholders to which value is distributed, and how a native token fits in.

Above — Trying to reason about the makeup of protocol tokens.

Protocol tokens might be the most defining facet of crypto’s first 12 years, but there remains a large amount of confusion surrounding their fundamental makeup.

I expect that the vast majority of protocol tokens will be productive assets. This simply means that like bonds, businesses, farms, etc, protocol tokens grant a claim on a stream of cash flow as yield.

Protocol cash flows are still relatively small, but the intrinsic value of a productive asset is the sum of all future cash that it can generate, discounted to the present. These are early-stage technology projects , so if successful, the lion share of cash generation lives in the future.

However, we can’t simply analyze protocol tokens in the same lens as traditional forms of productive capital. For one, protocols distribute cash flows directly to varying sets of market participants, as well as redistribute share of future cash flows between these participants.

Tokens can also grant access to distinct forms of non-cash flow-related utility, and can even be socially accepted as commodity money! Sometimes these additional demand pressures are quantifiable (i.e. a discount token), but often, we can only reason about them qualitatively. How much is governance over a widely integrated DeFi protocol worth to second layer projects, or during a fork choice?

In combination, tokens have intrinsic value as a claim—or a potential claim—on future cash flows, as well as a structural demand premium due to granted utility, monetary properties, or position in the stack.

In order to gain a better understanding of protocol tokens as a novel form of capital, it’s worth examining the piece that is quantifiably valuable: cash flows.

On-chain cash flows

A simple way for thinking about how value flows through protocols is as a three-tier model.

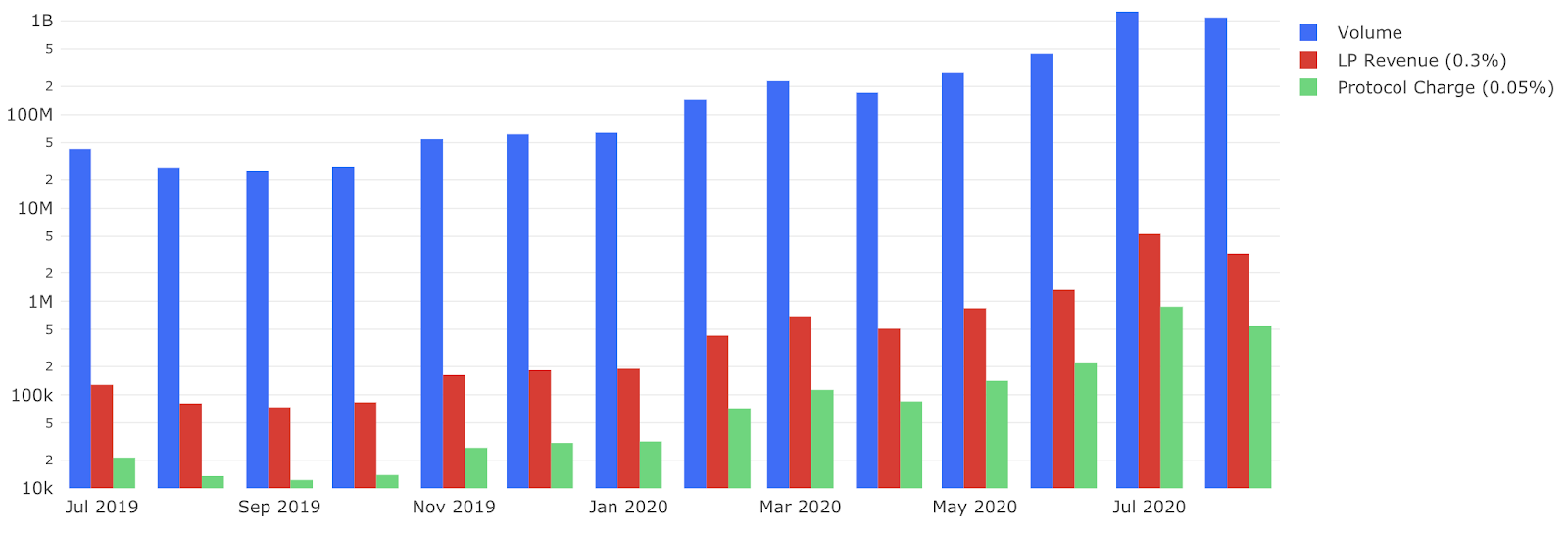

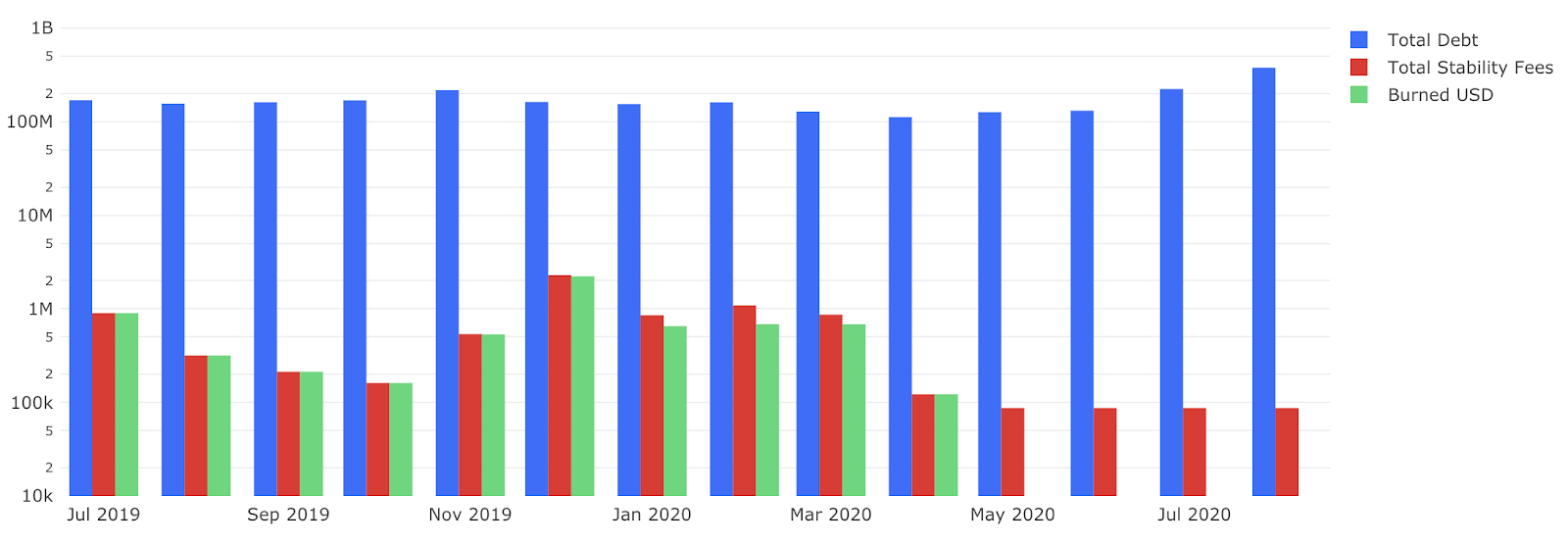

Above — Uniswap 3-tier Value Flow (Log Chart)

Tier 1: Protocols facilitate some amount of total notional volume.

For layer-1’s such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, this is the total value transacted. For DEX’s, this is exchange volume. For lending protocols, this is total outstanding borrows.

It’s simply a measure of the total dollar value of demand for a given service.

Tier 2: Protocols capture some portion of total facilitated volume as a revenue stream by charging a cost on users, which I’ll refer to as protocol revenue.

The way in which this revenue stream is generated largely depends on the structure of the given market, as well as the fee structure of a given protocol. With lending markets, compounding interest revenue is generated as a function of total borrows outstanding and prevailing interest rates, independent of borrow turnover.

Uniswap’s 0.3% protocol fee is proportional to exchange volume, while 0x generates fees as a function of trade frequency & Ethereum gas prices, largely independent of volume.

This potential disjointedness between total volume and fee charged revenue is why we can’t rely solely on protocol revenue as a means to see the full picture. A DEX could be doing $100M in monthly volume, but charging no trading fees on its users - clearly its potential to generate cash flow into the future is larger than 0.

Maker’s recent protocol revenue is low due to 0% stability fees being set for most collateral types, but *potential* cash flow from $420M in originated debt is high.

Tier 3: Protocols divvy up the total revenue stream and direct it to various participant groups within the market.

Protocols are often described as similar to cooperatives in that revenue share is allocated directly to market participants, rather than to a single margin-maximizing entity. This is why there is no easy way to define a blanket “earnings” metric – protocol stakeholders are far more diverse than shareholders of a business.

Protocol revenue distribution

It makes sense to classify four comprehensive sets of participants to which protocol revenue is distributed:

- Arbitrary supply-side participants (LP’s, lenders, miners, keepers/liquidators)

- Arbitrary demand-side participants (DSR depositors, Nexus Mutual claimers)

- Token-owning supply-side participants (PoS validators, 0x MMs, Keep signers)

- Token owners

A protocol token is a productive asset if the revenue share is distributed to either of the last two categories of participants. Namely, the token itself, or the token in combination with some service provision, grants claim on a stream of future cash flow.

It’s common today to see protocols distributing 100% of revenue to ‘arbitrary’ supply-side participants, where a native token is not required to provide the service, nor is revenue share distributed as a function of native tokens owned/staked by the service provider. Within DeFi protocols, this service is usually some form of liquidity provision. LP’s in both Balancer and Uniswap V2 (with no 0.05% protocol charge switched on) are distributed the entirety of protocol revenue.

Most PoW chains have a similar dynamic where all fee revenue is distributed to a non-token-owning supply-side: miners. Bitcoin miners can be thought of as “staking” coupons for future BTC in the form of mining hardware. This is why BTC would not be classified as a productive asset; the mining hardware, rather than the token itself, provides the claim on 100% of protocol revenue.

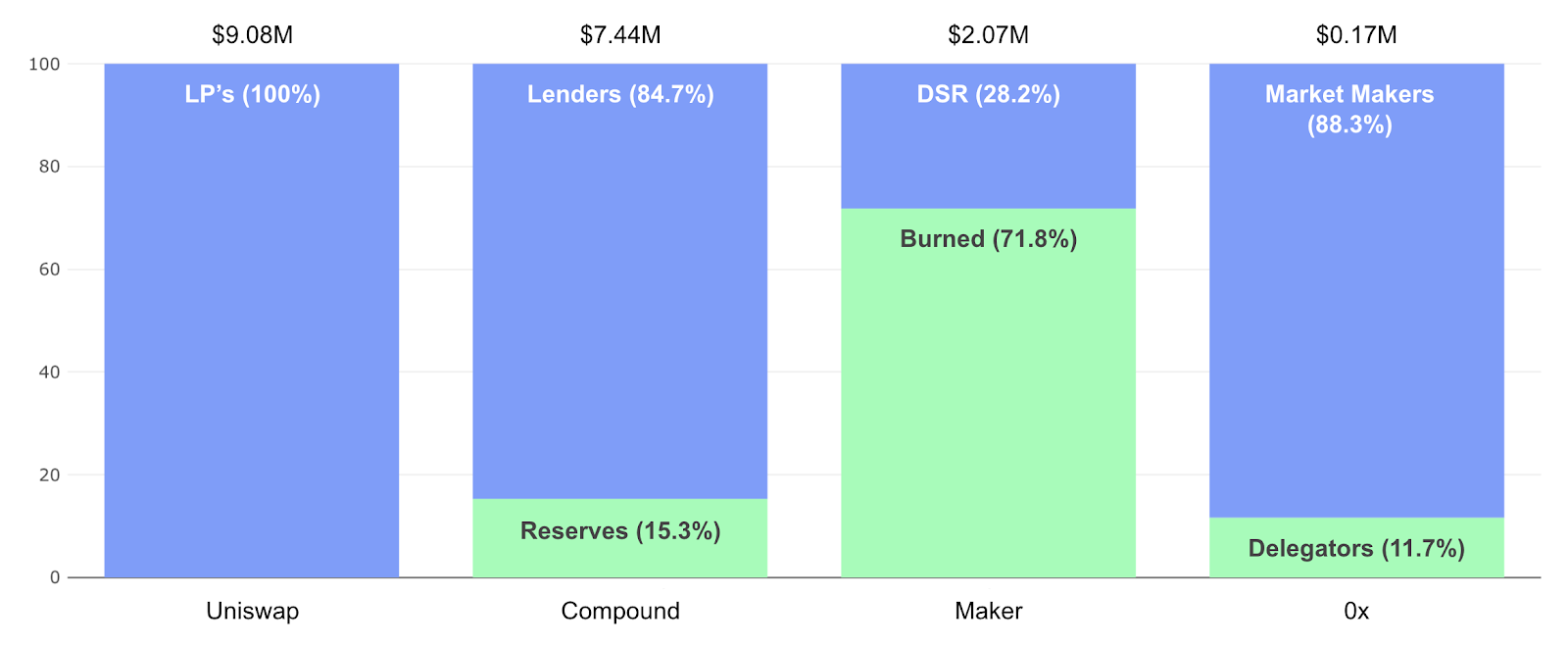

Above — Trailing 6-Month (Feb-Aug) Revenue & Distribution by Protocol

With regards to tokens that are productive assets, the most common model is paying out some share of protocol revenue to token owners as a dividend. Buy & burn mechanisms, like stock buybacks, are economically equivalent to receiving a dividend and using it to buy more shares. When tokens are burned with protocol revenue, the effective dividend is paid out to the entire base of token owners.

Staking rewards - specifically, the share made up by protocol revenue rather than a subsidy - is another form of a dividend. Unlike buy & burn models, the dividend is only paid out to token owning participants that are additionally providing a supply-side service: locking capital by staking the native asset.

The implied yield on capital receiving a buy & burn dividend is protocol revenue paid out / total supply * price, but with staking rewards, the calculation shifts to protocol revenue paid out / staked supply * price.

Protocols also tend to vary on the size of revenue distribution with the level of work provided by a given class of participants. 0x distributes protocol revenues to market makers (weighted by maker orders filled and a pro-rata share of tokens staked), of which, a sub-portion is paid out to token owners delegating stake to a given market maker.

Dynamic redistribution of future cash flows

The not-yet-existent Eth2 economics can help illustrate a case where both varieties of dividends exist in parallel. It’s important to note that subsidies such as block rewards are not productive cash flow, rather, they represent a dilution of future cash flows from existing holders to the subsidy recipient.

In the layer-1 specific case where a native asset is both productive and maintains a large monetary premium, issuance is somewhere between seigniorage and dilution.

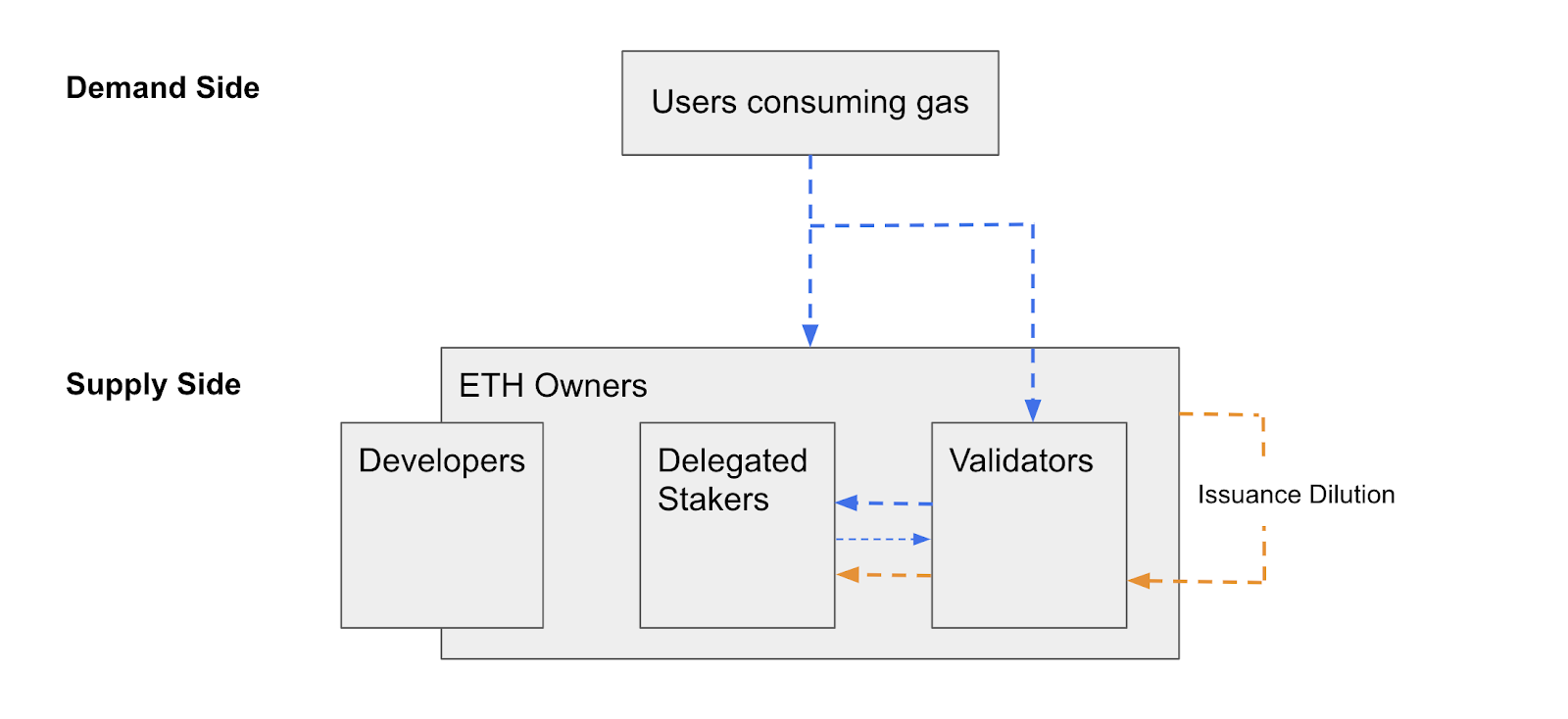

Above — Eth2 Cash Flow Distribution

Assuming that either EIP-1559 and/or ETH2 is successfully implemented, Ether would shift in makeup to a productive asset. This more broadly applies to all native assets of PoS chains. Both validators, and stakers delegating to validators, are members of the above participant set where token-ownership is required in order to perform a supply-side service.

The fee revenue portion of the staking reward (‘tips’) is paid as a dividend, where delegating stakers will likely receive a slightly smaller share than validators due to the presence of delegation fees. Ether burned as BASEFEE in EIP-1559 is another form of dividend, except it is paid out to all token owners. Validators and delegating stakers effectively “stack” both of these forms of dividend, receiving:

- The burned fee revenue, where the yield on capital is proportional to the percentage ownership of the total token supply

- The fee revenue rewarded to stakers, where the yield on capital is proportional to percentage ownership of total tokens staked

Considering these protocol revenue distribution dynamics in combination, we see something extremely interesting: the distribution of future cash flows is computationally rebalanced between participant classes in order of their importance to the protocol! [1]

- Validators

- Delegating stakers

- Token owners

Problems with dividend models

There’s a couple of problems with deterministically paying out protocol revenues as a dividend to token owners or token-owning supply-side participants. Buffet explains the first one, which applies to buy & burn models:

“Repurchases are sensible for a company when its shares sell at a meaningful discount to conservatively calculated intrinsic value … But never forget: In repurchase decisions: the price is all-important. Value is destroyed when purchases are made above intrinsic value.” [2]

Put simply, it makes sense to buy & burn when the asset is cheap and doesn’t when it’s expensive. Using protocol revenue to buyback a token that just pumped 10000% over the last month is probably not the most effective way to allocate surplus cash flow.

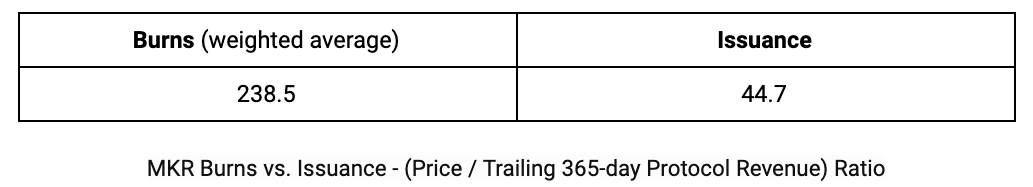

Historically, Maker has been short convexity, diluting owners (MKR flops) when the token is cheap and increasing share of future cash flows (MKR flips) at more expensive levels.

The other issue with paying out dividends is that you lose out on the natural compounding effect that businesses exhibit in their ability to reinvest retained earnings.

More optimal models

“Designed correctly, effective distribution of a fee stream can further entrench network effects by giving users a direct economic incentive to contribute, generating more defensibility, which in turn, reinforces the viability of the fee stream in the first place.” [3]

An optimal token model is one that:

- Incentivizes all sets of protocol participants to perform their given role (i.e. supply-side revenue) while minimizing costs to users

- Incentivizes all sets of protocol participants to own a single capital instrument as unified upside incentive

- Redistributes ownership of future cash flows to participants in order of importance

- Maximizes the effectiveness of retained cash flow allocation (possibly paid out to or claimable by the capital instrument) after accomplishing a, b, and c

As can be seen above in the Eth2 diagram, most protocols have not yet solved sustainable developer funding – a clearly crucial set of supply-side participants - but iterations on each of the last two points might serve as solutions.

We see an alternative model with Compound’s Reserves; the protocol retains surplus revenue as a governable, on-chain balance sheet.

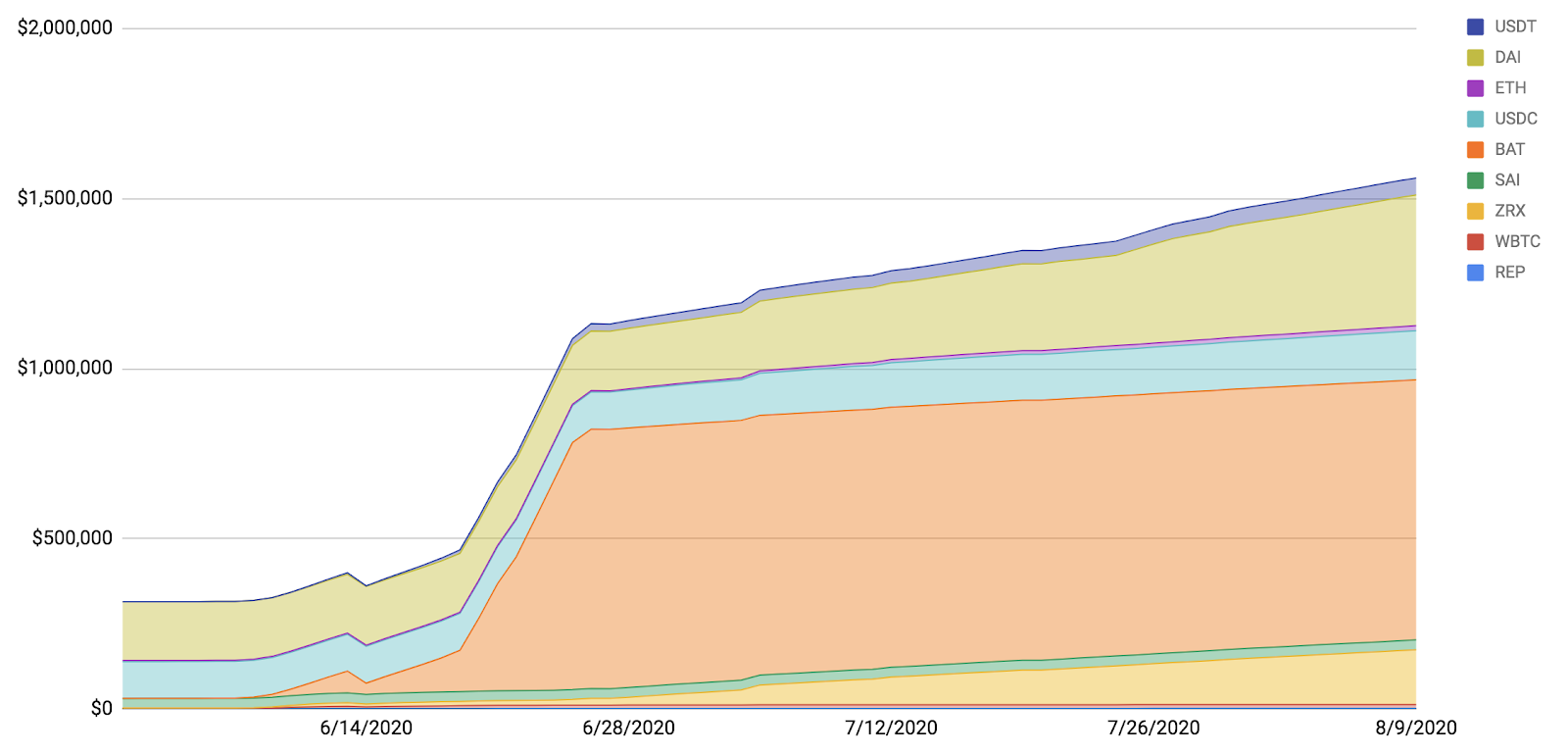

Above — Compound Reserves USD By Asset, post COMP subsidy

Reserves can be continuously lent out, improving the interest accrued by true lenders.

This grows Compound’s moat, propagating the feedback loop forward, ultimately resulting in more funds accrued as reserves. Through governance, COMP already grants an effective claim over reserves, so the question becomes: why pay out dividends when you can let retained cash flow accrue to an on-chain balance sheet and continue to compound?

Reserves are first and foremost used as an intra-protocol insurance cushion, but they could in theory be used for other things. Some safety margin could be determined by governance in order to skim off excess reserves and auction them for COMP as a buy & burn dividend when the price is favorably low.

But reserves could also function as a protocol treasury that is computationally rebalanced in order of importance to active contributors, voters, and delegators!

Dilution as funding & cash flow expansion

Protocols need to incentivize broader protocol goods, which include things like development, governing roles, and insurance. Allocation to these needs could very well contribute to a better return on capital over the long term vs. paying dividends.

This can be done using the distribution of present cash flows or allocation from a retained protocol treasury, but it can also be done through dilution of future cash flows as issuance.

MKR issuance through flop auctions is a model where dilution is used as an effectively limitless insurance backstop [4]. Tezos style issuance that rewards contributors for protocol upgrades are another potential use of dilution as funding - I could imagine Compound governors adding something similar if they thought it beneficial.

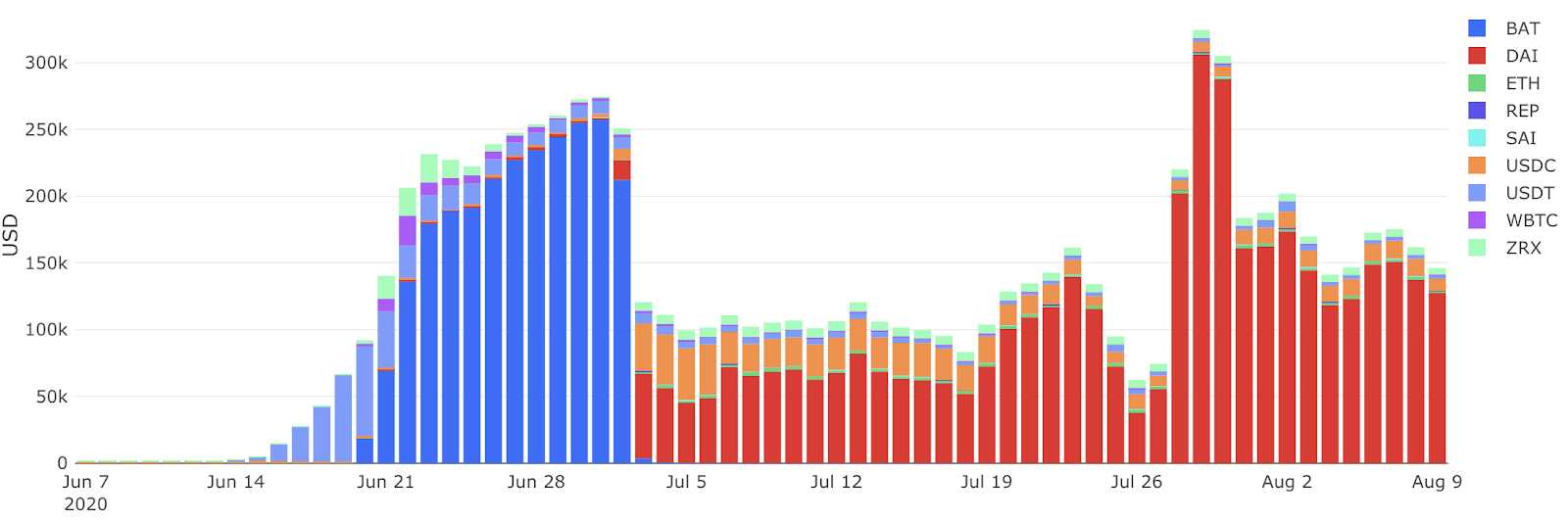

Liquidity mining uses dilution as a means of subsidizing an increase in supply-side liquidity, and ultimately demand-side volume (back to 3-tiered structure). Liquidity mining works dramatically over the short term to stimulate demand-side metrics, but the jury is out on how sticky it will be.

Above — Compound Daily Protocol Revenue by Asset, post COMP subsidy

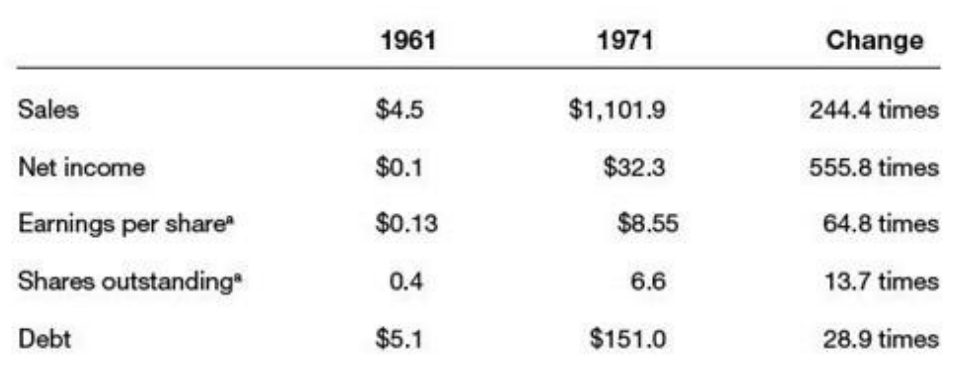

Liquidity mining as a growth strategy also reminds me of the story of Henry Singleton, CEO of Teledyne in the 60’s and 70’s. Over 8 years while Teledyne was trading at high multiples, he bought 130 companies – all but 2 acquisitions were made using his own stock. These were the returns during the period [5].

Above — Singleton returns during issuance spree

Then, Singleton abruptly changed directions. For the next 12 years, he bought back over 90% of outstanding stock at cheap multiples. Similarly to expanding sales through acquisitions, liquidity mining uses dilution to purchase demand-side volume.

Over the long term, protocols can bring future growth into the present through subsidy issuance and then ultimately capture some portion of that expanded value flow.

Thoughts on present & future

The crypto market seems to have reverted to its unfortunately natural state as a Keynesian Meme Contest, so it’s either the best time or the worst time to discuss fundamentals. A few of the recent dynamics can be described through the lens of cash flows.

Bull market valuations can only really be attributed to speculative premium, but cash flows have also historically increased by orders of magnitude during these periods. Last cycle, it was fee revenue on Bitcoin and Ethereum and the evidence is clear that this will repeat, but we are also seeing massive expansions in DEX volume, lending volume, etc.

It’s worthwhile to be wary of forward-looking “P/E” or “P/S” ratios.

They serve as a useful gauge of price vs. present cash flows, but not as a signal of historical cheapness. Depending on the trailing timeline, Ethereum’s Price / Forward-Looking Fee Revenue ratio has historically bottomed out when ETH was most expensive. Price / Trailing 365-day Fee Revenue (which due to on-chain data, can be annualized daily!) tends to serve as a more reasonable signal of cheapness, particularly when price is low as compared to the fee revenues of the previous cycle.

Above — Ethereum Price / Fee Revenue Ratio - Trailing 365-day (Log Chart)

In addition, we’ve seen dilution of a productive (or non-productive) asset as growth funding in liquidity mining. Subsidies happen to massively outcompete all other yields when assets are trading at large speculative premiums from day 0, and as we know, liquidity mining can produce a large increase in demand-side metrics (possibly legit, possibly not).

We also have seen a real-time “collateral premium” reflected in assets, due to both low liquidity and demand to chase these yields. Examples include BAT with Compound, all YAM farmable assets, etc. This is a further example of tokens as very much dissimilar from traditional forms of capital, like equity.

In addition to their value as productive assets, tokens can exhibit temporary or permanent demand premiums, one of which collateral-dependent yields in farming.

Thank you to Ash Egan, Teo Leibowtiz, Dan Elitzer, Hasu, Henri Hyvärinen, Henry Harder, Will Price, and Liam Kovatch for conversations & feedback on previous versions

Sources:

[1] Charlie Noyes on computational equity

[2] Buybackquotes

[3] Crypto’s Business Model is Familiar. What Isn’t is Who Benefits

[4] Tom Schmidt on the two token schools

[5] The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success

Action steps

Read our previous pieces on crypto capital assets:

Listen to a couple episodes on crypto capital assets:

Author Bio

Jon Itzler is a research intern at Accomplice — a technology-focused venture capital firm based out of Boston & San Francisco.

Subscribe to Bankless. $12 per mo. Includes archive access, Inner Circle & Badge.

🙏Thanks to our sponsor

Aave

Aave is an open source and non-custodial protocol for money market creation. Originally launched with the Aave Market, it now supports Uniswap and TokenSet markets and enables users and developers to earn interest and leverage their assets. Aave also pioneered Flash Loans, an innovative DeFi building block for developers to build self-liquidations, collateral swaps, and more. Check it out here.

Not financial or tax advice. This newsletter is strictly educational and is not investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell any assets or to make any financial decisions. This newsletter is not tax advice. Talk to your accountant. Do your own research.

Disclosure. From time-to-time I may add links in this newsletter to products I use. I may receive commission if you make a purchase through one of these links. I’ll always disclose when this is the case.