DeFi lending doesn't exist (yet)

Level up your open finance game five times a week. Subscribe to the Bankless program below.

Dear Bankless Nation,

Ever hear this?

“So I have to deposit 150% of my money to borrow back 100%…uh…that’s not a loan.”

It’s what crypto newbs say the first time you tell them about DeFi lending, right?

“It’s not like a credit card loan” you reply “it’s a collateralized loan like your mortgage.”

🤔🤔🤔

Loan.

That word. Have we warped its meaning in DeFi? If lending is about credit…and we’re not extending credit…are we really lending?

Do the crypto newbs have a point?

Jake thinks so.

He says things like Compound, Aave, Maker are more like interest rate protocols than lending protocols. No credit risk, no credit, no loan.

But that’s still amazing btw.

Because we’re rebuilding the financial system one lego block at a time!

Let’s not undersell what we’re doing here—this is the single biggest revolution to the financial system of our lifetimes. But let’s not oversell it either—we have many of the core money legos but there’s so much to build!

I think that’s Jake’s call to us today.

- RSA

P.S. We released Bankless tees & hoodies this week. Time to start repping the Nation 🏴

🙏Sponsor: Aave—earn high yields on deposits & borrow at the best possible rate!

THURSDAY THOUGHT

Guest Post: Jake Chervisnky, General Counsel at Compound Labs

DeFi Protocols Don’t Do “Lending”

DeFi protocols enable many types of permissionless financial services, but so far, lending isn’t one of them.

Decentralized finance (“DeFi”) has taken center stage in the crypto industry this year. One popular type of DeFi protocol has come to be known as the “lending” protocol, which allows users to supply and borrow digital assets at interest rates established algorithmically based on market forces of supply and demand.

Although the term “lending” is broadly used and easily understood in common parlance, it misrepresents the economic activity that these protocols enable. Users of these protocols do not extend credit or incur debt, which are the essential characteristics of a loan transaction. Users earn interest securely through overcollateralization and free market liquidation, not through lending.

This article explains how DeFi protocols mislabeled as “lending” protocols typically function, what the term “lending” actually means, why these protocols do not enable lending, and why it’s important to honestly and accurately describe what DeFi can and cannot do.

Disclaimer: I serve as General Counsel for Compound Labs, Inc. This post expresses my personal opinion and does not represent the views of my employer. This post is not and should not be considered legal or financial advice.

DeFi Replaces Institutions With Protocols

The ultimate vision for decentralized finance (“DeFi”) is a self-sovereign financial system allowing users to engage in a broad range of economic activities without the need to rely on trusted third parties. The base layers of the Bitcoin and Ethereum networks already achieve that vision for the simple activities of sending, receiving, and holding money. DeFi tries to go further.

The core idea is to take the complex financial services traditionally offered by legacy institutions, distill them into their component rules and procedures, and convert them into self-executing code — autonomous protocols that share the permissionless, non-custodial properties of the decentralized networks on which they reside. So far, DeFi developers have launched protocols enabling a wide variety of intermediary-free economic activities, including digital asset exchange, payments, portfolio management, derivatives trading, prediction markets, private transactions, and more.

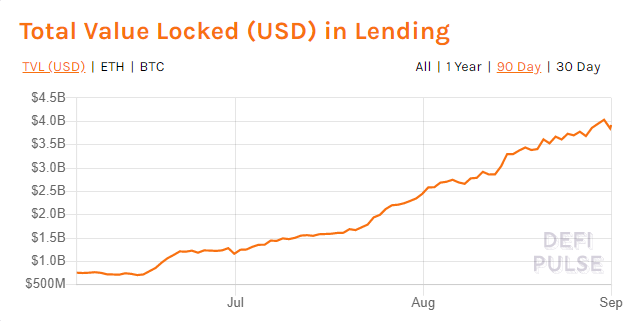

One popular DeFi category includes the so-called “lending” protocols, in which users can supply digital assets as collateral to earn interest, borrow other assets, and create stablecoins tracking the value of fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar. DeFi users have shown great interest in these protocols, with billions of dollars in capital inflows over the last few months alone.

(Above) Defipulse.com reports $3.92 billion locked in “lending” protocols as of September 1, 2020.

How So-Called “Lending” Protocols Work

There are several DeFi protocols commonly described as “lending” protocols, each of which has its own unique features and characteristics. Despite their differences, most depend on the same essential mechanics to function: overcollateralization and liquidation.

To use one of these protocols—which I’ll call “interest rate protocols” for convenience—users begin by supplying assets to the protocol as collateral. Supplying assets to a protocol could feel somewhat like depositing money into a bank account, except there’s no third party with custody over those assets ; users maintain exclusive control over their own assets at all times.

Users who have supplied assets to a protocol can then borrow other assets from the protocol up to a certain limit, which is always less than the amount of value in collateral that they supplied in the first place. Since users always have to supply more value in collateral than they can borrow, their positions are said to be overcollateralized.

If market conditions change so that a user’s position exceeds their borrowing limit — such as if the value of their supplied collateral falls, or the value of their borrowed assets rises — then their position can be liquidated. Liquidation occurs when a third party repays some or all of a user’s borrowed assets and claims the user’s supplied collateral as a reward, often at a discount.

For example,** imagine you want to use an interest rate protocol to borrow DAI using your ETH as collateral. You start by supplying $1,000 in ETH to the protocol. You can then borrow some fraction of that amount from the protocol in DAI, depending on the protocol’s borrowing limit . Assuming you use a protocol with a borrowing limit of seventy-five percent of the collateral supplied, you could pledge $1,000 in ETH as collateral for a borrowing position of $750 in DAI. Your position is then overcollateralized by $250.

Now imagine that the market price of ETH falls by four percent. Instead of $1,000, the ETH you supplied is now worth only $960. Your position is still overcollateralized by $210, but you’re now over the protocol’s borrowing limit — the $750 in DAI you borrowed is over seventy-eight percent of your ETH’s reduced value. This means your position is subject to liquidation by a third party, who can repay some of the DAI you borrowed until you’re back under the limit. Here, a liquidator might repay $150 in DAI and receive $160 of your ETH, earning $10 in profit and making your new position $600 DAI borrowed against $800 ETH ; seventy-five percent.

As you can see, the combination of overcollateralization and liquidation are designed to keep interest rate protocols solvent — that is, to prevent a situation where users can’t recover their supplied assets because other users borrowed them and failed to pay them back. As long as users’ positions are liquidated while still overcollateralized, these protocols won’t suffer a loss of funds, and users will be able to withdraw their supplied assets at any time. So far, this system has proven effective, securing billions of dollars in assets through the economic incentives of free market liquidation rather than through reliance on a trusted third party.

The Heart and Soul of Lending: Credit and Debt

Before we discuss why interest rate protocols don’t enable “lending,” we should first define the term “loan.” Put simply, a loan is a transaction in which one person gives money to another person who promises to pay it back later, typically with interest.*** Every loan involves at least two parties: the person giving money (the “lender” or “creditor”) and the person receiving money (the “borrower” or “debtor”).

For most people, lending is a familiar and ordinary aspect of financial life. You’ve probably made or received a loan at some point ; in fact, you’re probably a party to at least one loan right now. Maybe you took out student loans to pay college tuition or a mortgage to buy a house. Perhaps you make monthly payments on a leased car or a credit card. You might have loaned money to a friend or family member.

In all of these examples, as in every loan, the same basic element is at work: trust. When a creditor gives money to a debtor, the creditor trusts that the debtor will pay it back as promised. The government trusts you to pay your student loans; the credit card company trusts you to pay your monthly bills; you trust your friend or family member to pay back your money.

The essential role of trust in lending explains why we use the term “credit” in the first place. The term “credit” is rooted in the meaning “to believe” or “to put faith” in something, and it serves dual roles in the lending context:

- First, it refers to the money that a lender gives to a borrower. A lender “extends credit” by giving money to a borrower, or provides a “line of credit” by allowing the borrower to request money in the future.

- Second, it refers to a lender’s faith that a borrower will repay a loan, often based on the borrower’s reputation for reliability and solvency. A borrower who earns a lender’s trust is said to be “creditworthy” or to have “good credit.”

In short, credit is the essential feature — the sine qua non — of lending.

The Cost-Benefit of Credit and Debt

Importantly, every extension of credit is matched with a corresponding debt. Whereas credit describes a creditor’s trust that a debtor will repay their loan as promised, debt describes the debtor’s obligation to do the same.

As parties to a loan, creditors and debtors accept different costs in pursuit of different benefits.

The creditor, if all goes well, gets their money back plus the benefit of interest, which the creditor can book as profit. To obtain that benefit, the creditor pays an opportunity cost by tying up their money for the duration of the loan and loses the chance to spend or invest it somewhere else. The creditor also takes the risk that the borrower will default on the loan by failing to pay it back, resulting in the creditor losing some or all of their money. This risk is commonly known as “default risk” or “credit risk.”

The debtor, on the other hand, receives the benefit of spending the creditor’s money on costs that the debtor might not otherwise be able to afford. To obtain that benefit, the debtor pays a “cost of capital” in the form of interest, which typically accrues on a regular basis — often monthly, and sometimes weekly or daily — until the loan is repaid in full.

The debtor also takes the risk of failing to repay the loan, which can have a variety of negative consequences. Depending on the loan terms, the debtor may simply have to pay some added fees or penalties. In the worst case, however, a debtor can fall into a “debt spiral” in which interest accrues on outstanding loans faster than the debtor can pay them off. Debt spirals can ultimately lead to insolvency, bankruptcy, and financial ruin.

As you can see, default is the worst possible outcome for a loan — creditors can lose their money and debtors can go bankrupt. As a result, the finance industry has spent decades and billions of dollars creating a complex system for analyzing and quantifying default risk.

The best-known features of that system are credit scores and credit ratings, which represent the likelihood that a debtor will default on a loan. Credit scores and ratings consider factors such as the debtor’s payment history, amount of outstanding debt, and amount of available credit. In the United States, the major credit bureaus — Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion — produce credit scores for individual consumers, while the major credit rating agencies — Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s — produce ratings for companies and sovereigns.

Even with reliable credit scores and ratings, it’s impossible to completely eliminate the risk of default ; there’s just no way to be certain that a debtor will be able to repay a loan. To manage that remaining risk, a sophisticated creditor will typically require a debtor to sign a legal agreement that allows the creditor to “enforce the loan” if there’s a default. This means the creditor can sue the debtor in a court of law and obtain a judgment against the debtor for the outstanding amount of the loan. The creditor can use the judgment to seize other assets belonging to the debtor to satisfy the loan as well.

Now that we’ve covered the mechanics of interest rate protocols and the essence of credit-based lending, we’re ready to put both concepts together and explain why DeFi lending doesn’t exist — at least not yet.

DeFi Fundamentally Doesn’t Do Credit or Debt

So far, we’ve discussed (1) how the core feature of lending is a creditor’s ability to trust a debtor to repay a loan, and (2) how the core purpose of DeFi is to remove trust as a requirement for financial activity. As you can see, these systems take opposite approaches to the issue of trust.

Indeed, interest rate protocols are designed not to involve trust at all. As explained above, their solvency and soundness depends on the mechanics of overcollateralization and liquidation, not on the expectations and promises of credit and debt.

Remember that credit describes a lender’s trust that a borrower will repay a loan, typically based on the borrower’s reputation for reliability and solvency. Unlike lending, suppliers of assets to interest rate protocols do not trust borrowers to repay borrowed assets — in fact, they usually don’t know the borrowers at all. There are at least two reasons for this:

- First, like the decentralized networks on which they reside, interest rate protocols are permissionless by default, meaning they can be used pseudonymously by anyone with access to the internet. This means it’s difficult or impossible for suppliers to tie a real-world identity to a particular borrower without using a blockchain analytics service.

- Second, DeFi transactions are conducted on a “peer-to-pool” or “peer-to-protocol” basis, meaning users supply and borrow fungible assets to and from a pool of liquidity stored within the protocol, not to and from specified counterparties. This means it’s difficult or impossible for suppliers to identify any particular borrower who can be said to have borrowed their assets rather than the assets of another supplier.

Instead of relying on their trust in borrowers, suppliers rely on overcollateralization and liquidation to ensure that they can withdraw their assets at any time. Borrowers always have to supply more value in collateral than they can borrow, and suppliers can always seize that collateral — or have it seized on their behalf — through a free and open market for liquidation. These mechanics work exactly the same way regardless of the borrowers’ creditworthiness.

Remember also that debt describes a debtor’s obligation to repay a loan. Unlike lending, borrowers of assets from interest rate protocols do not have any obligation to repay the assets they borrow — in fact, borrowers don’ t have to make any further payments whatsoever.

Instead of receiving the benefit of spending someone else’s money based on the promise of repayment, DeFi borrowers supply in advance more than the entire amount they may later owe. Borrowers are then free to walk away and never repay the assets they borrowed without posing any additional risk to suppliers. In doing so, borrowers forfeit their collateral to eventual seizure through liquidation. Either way, the protocol is designed to return suppliers’ assets in full.

Put differently, overcollateralization and liquidation are intended to eliminate default risk. Suppliers don’t have to worry that borrowers will fail to repay their loans because it doesn’t matter if borrowers make repayments in the first place; by design, suppliers should get their money back regardless. This is not to say that interest rate protocols are entirely free from all risks, but simply that they do not pose default risk, which characterizes lending.

In short, because interest rate protocols don’t involve credit or debt — and because they do not depend on trust or expose users to default risk— the transactions they enable are not loans.

DeFi Doesn’t Do Secured Lending Either

It’s worth acknowledging that collateralization is not unique to interest rate protocols — it plays a critical role in lending as well. Nonetheless, the DeFi transactions that we’ve discussed here are categorically different from collateralized loans.

In an unsecured loan, creditors rely solely on their trust in debtors to repay loans, plus their trust in courts of law to enforce those loans if a debtor defaults. In a secured loan, creditors also take an interest in specific assets pledged by debtors as collateral for the loan. If a debtor defaults, a creditor can try to use the collateral to cover their loss as well.

But the presence of collateral in secured lending doesn’t change its fundamental character —it still depends on credit and debt. Secured creditors still develop relationships with specific debtors whom they trust to repay loans, often using credit scores and ratings to assess debtors’ creditworthiness. Debtors who pledge collateral still promise to make future payments according to the loan terms, and cannot simply walk away after taking a creditor’s assets. The loan is still subject to default risk, which can have serious consequences on both sides of the transaction.

Mislabeling DeFi Protocols Is Bad for Everyone

If you’ve made it this far, you may be wondering why it’s worth so much time to draw what may appear to be a semantic distinction, an unnecessary academic exercise in the policing of language. The term “lending” is easy for the public to grasp, so who cares if it isn’t technically accurate?

We should all care. Far from mere semantics, it’s critically important to the future of DeFi that we accurately describe what we’re building and honestly admit the limitations we’ve yet to overcome.

Over the last few months, the typically thoughtful and steady DeFi space has begun showing signs of speculative mania reminiscent of the initial coin offering (“ICO”) bubble of 2017. That bubble was caused in part by developers who overpromised the potential of blockchain technology to solve all of the world’s problems while soliciting investments from the unsuspecting public. Nearly all were failures, and a number were frauds.

Although DeFi differs from ICOs in crucial ways—for example, our industry standard is to build fully-functional protocols out of the gate— the danger of irrational market behavior is much the same. There’s no way to stop people from taking risks with their assets, but we can at least help them make informed decisions. That means accurately explaining what DeFi protocols can and cannot do, and honestly admitting the limits of how disruptive they can be.

In the context of the protocols discussed here, it’s important to recognize that the market for overcollateralized borrowing is not the same as the much larger market for credit-based lending. It would be truly remarkable if any innovative technology could disrupt the multi-trillion dollar global credit market, but we should be careful to avoid such a grand promise until and unless we know DeFi is up to the task.

Also, the term “lending” undersells the unique benefits and advantages that interest rate protocols offer. When most people consider taking out a “loan,” they immediately and correctly think about the notion of going into debt. We do a disservice to these protocols by invoking that prospect, along with all of the risks that it entails.

By acknowledging that interest rate protocols don’t compete with credit markets, we earn the right to celebrate their ability to generate yield without subjecting users to credit risk. DeFi protocols don’t do lending, and that’s a good thing!

** This example is a simplified hypothetical for illustrative purposes only, and would likely play out in somewhat more complex fashion under live conditions.

*** For a more formal definition, the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines the verb “lend” as “to give for temporary use on condition that the same or its equivalent be returned” or “to let out (money) for temporary use on condition of repayment with interest.”

Action steps

Identify the difference between interest rate protocols & lending protocols

More Bankless pieces on DeFi “lending”:

Author Bio

Jake Chervisnky is the General Counsel for Compound Labs, the development team behind prominent DeFi interest rate protocol, Compound.

Subscribe to Bankless. $12 per mo. Includes archive access, Inner Circle & Badge.

🙏Thanks to our sponsor

Aave

Aave is an open source and non-custodial protocol for money market creation. Originally launched with the Aave Market, it now supports Uniswap and TokenSet markets and enables users and developers to earn interest and leverage their assets. Aave also pioneered Flash Loans, an innovative DeFi building block for developers to build self-liquidations, collateral swaps, and more. Check it out here.

Not financial or tax advice. This newsletter is strictly educational and is not investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell any assets or to make any financial decisions. This newsletter is not tax advice. Talk to your accountant. Do your own research.

Disclosure. From time-to-time I may add links in this newsletter to products I use. I may receive commission if you make a purchase through one of these links. I’ll always disclose when this is the case.